Patient Radiation Education

Introduction to (ionizing) Radiation

What is (ionizing) radiation?

Radiation is any energy that comes from a source and travels through space,

such as light or heat. However, when we use the term "radiation"

in medicine, people usually mean high energy "ionizing radiation".

Examples of ionizing radiation include x-rays and nuclear radiation (gamma

rays) from radioactive substances. Ionizing radiation can be used to provide

highly detailed images of the body, allowing for better diagnosis and

treatment. When carefully used, ionizing radiation in diagnostic imaging

provides many benefits with little risk.

Where does radiation come from?

All of us are exposed to (ionizing) radiation every day, mainly from the

sun and soil. Manmade sources of radiation include diagnostic imaging

tests (x-rays, CT scans, and nuclear medicine studies) and nuclear power stations.

How is radiation measured?

Radiation dose to the body is measured in units known as milliSieverts

(mSv). The small amount of background radiation we all receive every year

is about 3 to 5 mSv.

Benefits of Radiation

Many tests performed in the Department of Radiology use small amounts of ionizing radiation. Your doctor has requested these tests to better diagnose and manage your condition These tests are very different from radiotherapy in which much higher doses of ionizing radiation are used to treat cancers, because radiation can be targeted to kill cancers. Radiotherapy is performed by the Department of Radiation Oncology. Modern imaging allows for earlier and more accurate diagnosis, so that patients can be better treated and have better outcomes. For example, in a randomized study at Addenbrooke's Hospital in Cambridge, England, patients admitted because of severe abdominal pain were randomized to have a CT scan within 24 hours of admission or to have standard care. None of the 55 patients who got an early CT scan died, compared to 7 who died in the group of 63 patients who did not get an early CT scan [1]. Such studies indicate the benefits of diagnostic tests using ionizing radiation are real and not just theoretical.

- Ng CS, Watson CJ, Palmer CR, See TC, Beharry NA, Housden BA, Bradley JA, Dixon AK. Evaluation of early abdominopelvic computed tomography in patients with acute abdominal pain of unknown cause: prospective randomised study. British Medical Journal 2002; 325: 1387-1390.

Risks of Radiation Put into Perspective

It is generally assumed that low doses may also cause cancer. Most of the data on the cancer risk from radiation comes from studies on Hiroshima and Nagasaki Atomic Bomb survivors who were exposed to high doses of radiation [1]. The survivors definitely had an increased risk of cancer later on in life. The number of atomic bomb survivors who were exposed to low doses of radiation is not large enough to prove an increased risk with scientific certainty. Instead, scientists have extrapolated the risk for lower medical doses of radiation from the risk observed at high total body doses received by atomic bomb survivors.

This is a safe and cautious approach, and is the approach taken by the FDA [2]. Using such extrapolations, it has been calculated that the lifetime risk of a fatal cancer after a radiation dose of 10 mSv is approximately 1 chance in 2000 [2]. However, it is important to realize that this remains a "guesstimate" and no one knows for sure if low dose radiation is dangerous. The risk of low dose radiation is controversial, with conflicting articles in the medical literature [3, 4]. The controversy centers on whether it is correct to extrapolate low dose risk from high dose risk observations. For example, we all know that driving at 100 mph is dangerous, but would it be right to assume that driving at 10 mph is 1/10 as dangerous?

- Pierce DA, Shimizu Y, Preston DL, Vaeth M, Mabuchi K. Studies of the mortality of atomic bomb survivors. Report 12, Part I. Cancer: 1950-1990. Radiation Research 1996; 146: 1-27.

- Radiation Emitting Products and Procedures / Medical Imaging / Medical X-Rays

- Little MP, Wakeford R, Tawn EJ, Bouffler SD, Berrington de Gonzalez A. Risks associated with low doses and low dose rates of ionizing radiation: why linearity may be (almost) the best we can do. Radiology. 2009; 251: 6-12.

- Tubiana M, Feinendegen LE, Yang C, Kaminski JM. The linear no-threshold relationship is inconsistent with radiation biologic and experimental data. Radiology 2009; 251: 13-22.

Risk / Benefit Considerations

A 1 in 2000 chance of developing a fatal cancer after a radiation dose of 10 mSv (which is the kind of dose associated with many CT scans) may seem high. Such risks must be considered in context; virtually all medical procedures and tests carry both risks and benefits, and any consideration of risk must be balanced against the benefits. The benefits of CT and other imaging tests using ionizing radiation are earlier diagnosis and treatment. Many of the amazing advances developed in the modern American medical system require tests using ionizing radiation to confirm diagnoses, plan management, and monitor the response to treatment. Undue anxiety about the cancer risk of radiation could potentially expose patients to far greater risks from delayed diagnosis or incorrect management.

Risk Comparisons

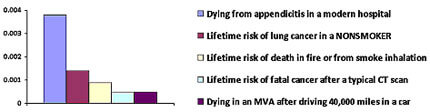

The amount of radiation during a typical body CT scan (10 mSv) is about the same as the radiation we get every two years from background sources, and the risk of getting a fatal cancer from this amount of radiation is about 1 in 2000. This may sound like a lot, but the graph below puts this risk in the context of other risks that are of similar magnitude. Notice that a patient who never smoked is more than twice as likely to die from lung cancer as from a cancer caused by a typical CT scan.

|

- Andreu-Ballester JC, González-Sánchez A, Ballester F, Almela-Quilis A, Cano-Cano MJ, Millan-Scheiding M, Ruiz Del Castillo J. Epidemiology of Appendectomy and Appendicitis in the Valencian Community (Spain), 1998-2007. Digestive Surgery 2009; 26: 406-412.

- Villeneuve PJ, Mao Y. Lifetime probability of developing lung cancer, by smoking status, Canada. Canadian Journal of Public Health 1994; 85: 385-8.

-

http://www.livescience.com/environment/

050106_odds_of_dying.html#table - National Highway Traffic Safety Administration website. Fatality Analysis Reporting System. http://www-fars.nhtsa.dot.gov/Main/index.aspx. Accessed February 14, 2010

Alternative Perspective

Another way of thinking about risk is to focus on the likelihood that something will not happen, rather than the odds it will happen. For example, a 1 in 2000 risk of cancer means a 99.95% chance of not getting cancer.

- Cohen BL. Cancer risk from low-level radiation. AJR 2002; 179: 1137–1143.

- Cohen BL. J Am Phys and Surg 2008; 13: 70-6.